18.11.2004 – 22.01.2005

SIMONE RACHELI – Anatomica Colf

curated by Raffaele Gavarro

On Thursday 18 November Antonio Colombo Arte Contemporanea opens a solo show by Simone Racheli, entitled Anatomica Colf (anatomical home-help).

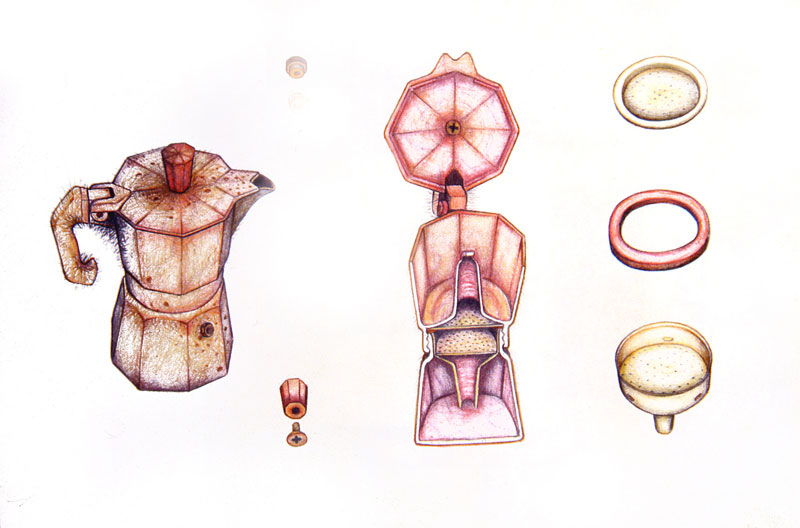

The exhibition, curated by Raffaele Gavarro, includes a series of drawings, sculptures, objects and installations that describe a domestic environment subjected to the transforming effects of the imagination.

The presences range from a washing machine with an altered housing, the work that gives the show its name, in which the window becomes a rotating iris, to Ricominciamo (Let’s start again), an installation formed by household objects that have been destroyed and put back together with glue and wire. Cuts in the wall reveal the wiring-guts that run invisibly below the surface, reinforcing the domestic shell, while Resistenza (Resistance), a small table that continues to stand, perfectly, though three of its four legs have been sawn off, becomes the visual paradigm of absurd, unpredictable everyday balances.

Of course the “home” must have its television set. In this case it broadcasts a video showing drops of water falling into a pool, which turns out to be an interior view of a toilet. The drops punctuate the autobiographical tale of an immigrant woman.

Born in Florence in 1966, Simone Racheli, who lived in Rome for several years before moving to Parma, uses sculpture in increasingly sophisticated ways involving extraordinary qualities of imitation of reality. Especially in Anatomica Colf, the staging of these works, contaminated by different languages, takes on great narrative power and complexity.

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue with a text by the curator.

Simone Racheli. Born in 1966 in Florence, lives and works in Parma. Solo shows: 2003 Check point, curator Andrea Bellini, Galleria Autoricambi, Rome. 2001 Domestica, curator Salvatore Galliani, Studio Ghiglione, Genoa. 1999 Un’opera, curator Augusto Pieroni, Delphine & Ludovico Pratesi, Rome. 1998 Naturalmente, curator Augusto Pieroni, Galleria Maniero, Rome. Selected group shows: 2004 P.C./A.C. – KALS’ART, curators Giuliana Stella, Laura Garbarino, Matteo Boetti, Ex Deposito Locomotive S. Erasmo, Palermo; Arte italiana per il XXI sec., Lorenzo Canova, Palazzo della Farnesina, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Rome. 2003 XIV Quadriennale-Anteprima, Palazzo Reale, NA; Alto volume corporale, curator Gianluca Marziani, Palazzo Bice Piacentini, Centro arte contemporanea, S.Benedetto del Tronto, AP. 2002 Exit, curator Francesco Bonami, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, TO. 2001 Laboratorio materiale, curator Luca Beatrice, Chiesa del Suffragio-Galleria Astuti, Fano-Pesaro; Ultracorpi, curator Maurizio Sciaccaluga, Chiostro di S.Agostino, Pietrasanta, MS. 2000 Mumble Mumble, curator Augusto Pieroni, Galleria d’arte Contemporanea, Castel S.Pietro Terme, BO; Sui Generis, curator Alessandro Riva, P.A.C., Milan. 1999 Arte duemila, curator Ludovico Pratesi, Temple Gallery, Rome. 1998 La raccolta dei mille progetti, Accademia di Francia Villa Medici, Rome; 1997 In che senso italiano?, curator Matteo Boetti, Galleria Anna D’Ascanio–Galleria Autorimessa, Rome and, in 1996 Realtà giovane, Galleria Civica d’Arte Contemporanea, Suzzara, MN.

The predictable otherness of things (home sweet home)

Raffaele Gavarro

Art stays home. In slippers, stretched out on the couch in front of the TV. No thought of going out for a breath of fresh air or a date.

It makes sense, if you consider everything that is happening out there in the world today.

Art doesn’t feel comfortable at all in wartime. Who or what, after call, could feel the slightest calm in a situation of such general danger and incomprehensible reckonings?

So art stays home, though actually, from there, it sends plenty of messages to the world outside.

The home, the private, domestic dimension represent places and conditions that are, in a certain sense, universal. Besides the extraordinary standardization generated on a worldwide scale by Ikea, what interests us is the possibility of immediate comprehension when we speak of the physical, mental and emotional place that preserves us and the things we care about. In a moment in which the private sphere is being almost totally co-opted by the continuous public exposure imposed by the mass media system, art reacts by defending vital space, transforming the subject into a declaration that may not be strictly political, but certainly has social value.

The nostalgia you can sense, like a sort of white noise, in any work involving this dimension is the inevitable residue produced by awareness of loss, leading to reflection, even when irony is one of the main tones of the orchestration.

Simone Racheli is an artist who chooses to begin with very simple project coordinates, though very sophisticated in their technical resolution, and manages to make the initial conceptual elements coincide with the imagery. Her experience with sculpture and installations involves imitation of reality. This leads, on the one hand, to the clear, immediate identification of the subject-protagonist, and on the other to an intrinsic technical difficulty in its reproduction, augmented by the imaginative shift from the position it usually assumes in everyday life. Minimal shifts that decontextualize the subject with respect to the environment in which it is placed, but above all modify that environment itself. The old trick of surrealism, which from being the great poetic forefather of modernity and postmodernity has wound up penetrating everyday reality, taking the form of neurotic, obsessive plots. The banality of the everyday world conceals the grand design, the conspiracy understood only by the few, while the majority becomes the unwitting victim. Just consider all the extraordinary literature – from Thomas Pynchon to David Foster Wallace, Philip Dick to Don DeLillo, but also Viktor Pelevin, William Vollmann, Jonathan Lethem, Steve Erickson, Ray Loriga, Douglas Coupland, Matt Ruff – that moves along the coordinates of this surrealism made paranoid by its perfect insertion in reality, and consider how these pages have then fed our collective imagery through cinema and television, with significant reflections, of course, in the visual arts.

If an appliance designed by Racheli is not just an appliance, but an unknown body to be dissected and studied in its various possibilities of meaning, this undoubtedly results from and is a part of that imagery.

Anatomica Colf can be seen as a single body, a single work that extends through various elements, parts of a body-home that refer to a banal reality principle captured in all its typical essence. The washing machine with the hypnotic porthole-eye is right there in everyone’s home. Spellbound by its multicolored spinning, we are enthralled by a useless thought, or we recall something that happened to us, something we had previously thought was unimportant. We suddenly understand that life, reality is not what we are experiencing, that we are in a sort of parallel plane without any hope of deciding our own fate. The click at the end of the cycle suddenly awakens us from our reverie, and we forget everything that seemed so clear just a minute ago.

A mystery, the washing machine is undoubtedly a mystery, a kind of black hole in our consciousness in which odors, moods, profound reflections on our existence are lost forever.

Around this center, through the effects of centripetal force, moves the everyday flow of events in the home, just as the objects of our tranquil everyday existence are arranged around it. Ricominciamo (Let’s Start Over) is the physical memory of a dramatic moment. A fight, the violence that destroys objects that were lovingly purchased, cared for and used, and the subsequent regret. We are looking precisely at the evocation of this sentiment. All the objects are patiently reassembled, sewn up, but their wounds remain visible, bearing witness to the irreversibility of the event, in spite of it all. Or this is something that has happened only in the head of our hypothetical lone protagonist, who then decided to make it real, to make reality and vision coincide, in order not to have to admit that the two are irremediably disassociated, at this point.

The inclined plane of surreal paranoia permeates the entire space of the home-gallery, encountering moments of great tension in the opening in the wall revealing its concealed system of wires. But there is also self-irony, as in Resistenza (Resistance), a small table with three of its four legs sawed off, which remains calmly standing, defying the laws of physics and patience. The narration of the place is modulated by this continuous alternation of tension and irony. This is a result of the intention – declared and aware of the partiality of the results – to emulate life. A flow of events that is never constant, regulated by the unknown factors, by what will happen one second later. A condition symbolically conveyed by this intertwining and permutation of very different moods. One good example is the video that ideally completes the itinerary of this voyage in the home. The television, after all, is another focal point of the home, though much less mysterious than the washing machine’s porthole. Instead of stimulating the production of paranoid images, the television inundates us with images that are already sufficiently packed with neurosis on their own.

This time the story that reaches us through the TV screen is that of a drop of water that falls into a clear pool. The surface vibrates with concentric circles, waves caused by the drop, while the voice of a woman, clearly a foreigner, speaks of the difficulties of an immigrant’s life. With each drop comes a piece of the story, becoming a veritable cascade. The camera pulls back, the frame widens, and we see that we are inside a bathroom, where someone has, of course, just flushed the toilet.

Anatomica Colf coincides with a significant change in the approach with which Racheli conceives and implements her representation of the world. As opposed to the works in which she sought out a direct confrontation with events, constructing hyper-realist characters, for example, in a parody of the actions of real people, or creating decidedly implausible situations with perfect credible elements, her way of working has become more complex. The game of realistic-improbable has become more subtle and detailed. The overall sense of the works itself is the clear consequence of a design that aims to achieve a continuity that is not only narrative, but above all conceptual. The extraordinary quality of Racheli’s works lies precisely in this dual endeavor: on the one hand, to construct a plane parallel to reality, perfectly credible in its reality and its configuration as image; on the other, to fill it with that substance of ideas and imagination that makes it plausible in its otherness, in its different dimension with respect to everyday reality.

A perfect paranoia in our present time.